...and I will wear him in my heart's core…”

― William Shakespeare, Hamlet

As I reflected on this week’s revelations out of Washington, D.C. and earlier in the month from Paris, France, I recalled a trip on the river Thames and visit to Cliveden, and I ask myself, who does political sex scandal better than the British?

Charles Stewart Parnell and Kitty O'Shea, Jeffrey Archer, but the biggest sex scandal ever in Britain was the Profumo Affair. By the time the dust cleared, the Prime Minister had resigned due to 'ill-health' and the Labor party was swept into office with Harold Wilson as its leader and new Prime Minister.

It was before the swinging 60's before the Beatles and the Rolling Stones launched a British invasion. 1960 was the year that the publisher Penguin was prosecuted for publishing D.H. Lawrence's novel Lady Chatterley's Lover. Penguin won the case and was able to publish 200,000 copies. People raced to get theirs. Ian Fleming's spy novels hit the screen starring sexy Sean Connery as 007. The newest actors in Britain were not Hollywoodized versions of British men, but actors like Albert Finney and Michael Caine. New magazines like Private Eye which poked fun at everyone and everything was established. Beyond the Fringe starring Peter Cook, Alan Bennett, Dudley Moore and Jonathan Miller hit the West End. And David Frost became a national celebrity hosting the hit TV show That Was the Week that Was.

Politically however, things were much less progressive. Although Harold Macmillan had swept into office in 1959 with a majority in the House of Commons, discontent ruled the country. The British economy was stagnant there was inflation and labor unrest. Unlike America, with its young, vibrant president the politicians in office reflected a by-gone era, the era of Churchill and Lloyd-George, old school politicians.

It also was the height of the Cold War, and Britain was reeling from the revelations that Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean were Soviet spies. In 1963, Kim Philby would be revealed as the Third Man in their spy ring and would also defect to the Soviet Union and the idea that a British politician was not only cheating on his wife, but sharing her with a Soviet diplomat did not sit well.

The chief players in the drama:

John Profumo - Secretary of State for War

Harold Macmillan aka Supermac - Prime Minister of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

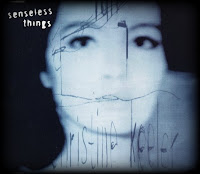

Christine Keeler - goodtime girl and model

Mandy Rice-Davies - fellow goodtime girl and model

Stephen Ward - osteopath and panderer

Lord Astor - owner of Cliveden, the estate where the shenanigans took place

Yevgeny "Eugene" Ivanov - senior naval attache at the Soviet Embassy

In the summer of 1961, Ward held a pool party at Cliveden.

At this party Christine Keeler met John Profumo, the British Secretary of State for War. He was highly regarded in the Conservative party having won his first election in 1945, becoming the youngest MP.

Profumo and Christine started having an affair, but what he didn't know at the time was that Christine was also sharing her favors with Yevgeny Ivanov, among many others. But it was Ivanov who was the problem. It turned out that Ward was involved in helping MI-5 to entrap Ivanov. Sir Norman Wood warned Profumo about his affair with Keeler, and to warn him to be careful around Ward who was known to be indiscreet. When MI-5 tried to recruit Profumo to help them trap Ivanov by compromising him sexually, so that Ivanov would be encouraged to either defect or pass secrets, and informed him that Keeler was also involved with Ivanov, Profumo refused. Instead he dropped her but the damage was done.

The affair came to light when Christine Keeler was involved in a shooting incident at the home of Mandy Rice-Davies. Hearing the commotion, someone called the police, and soon the flat was crawling with police and reporters.

The press began to investigate Keeler, and soon found out about her simultaneous affairs with Profumo and Ivanov. Because of Ivanov's connection to the Soviet Embassy, a simple sexual affair took on a National Security Dimension.

Things might have turned out differently if Profumo hadn't made the fatal mistake of lying to the House of Commons. Instead in March of 1963, Profumo told the House that there was "no impropriety whatever" (sounds familiar?) in his relationship with Keeler and to make matters worse he said that writs would be issued for libel and slander if the allegations were repeated outside of the House.

Things might have turned out differently if Profumo hadn't made the fatal mistake of lying to the House of Commons. Instead in March of 1963, Profumo told the House that there was "no impropriety whatever" (sounds familiar?) in his relationship with Keeler and to make matters worse he said that writs would be issued for libel and slander if the allegations were repeated outside of the House.

Profumo's denials didn't stop the press from continuing with their stories. On June 5th, Profumo finally admitted that he had lied to the House, which was an unforgivable sin in British politics. He not only resigned from office but also from the House as well. Before his public confession, Profumo told his wife. In spite of the scandal, it was never proven that his relationship with Keeler had led to a breach in national security (presumably Profumo was too busy doing other things to whisper state secrets to his lover). Profumo never talked about the scandal for the rest of his life, even when the movie Scandal came out in 1989, and when Keeler published her memoir of the affair. He died in 2006 at the age of 91, after receiving the OBE from the Queen. Like so many disgraced politician he learned that career rehabilitation was entirely possible.

The biggest fallout of the scandal was not Profumo, but Stephen Ward, who was prosecuted for living on immoral earnings. To make matters worse MI-5 denied that Ward had informed them of Keeler's affair with Profumo and Ivanov. On the last day of his trial, he took an overdose of sleeping pills. He was in a coma when the jury reached its verdict, that he was guilty. He died a few days later from the overdose. Harold Macmillan resigned in September of 1963 due to ill health. He was replaced by the foreign secretary, Sir Alec Douglas Home.

An official report was released 2 months after Stephen Ward's death. Hundreds of people queued up for copies. But like the Warren commission or the Starr Report, or…there was no dirt to be had, just a lot of criticism for the government failing to deal with the affair quickly.

The Profumo Affair opened the door in Britain to the type of tabloid journalism it would become infamous for. No more were public persons coddled, their foibles covered up by the press. It was open season. Ah well, the more things change…

Set down in what was once a rugged landscape,

Pasadena, California’s Church of the Angels is a little bit of home. At Christmas, children’s faces light the way

and angels come out of the woodwork.

Set down in what was once a rugged landscape,

Pasadena, California’s Church of the Angels is a little bit of home. At Christmas, children’s faces light the way

and angels come out of the woodwork.